Cropsey on natural slavery

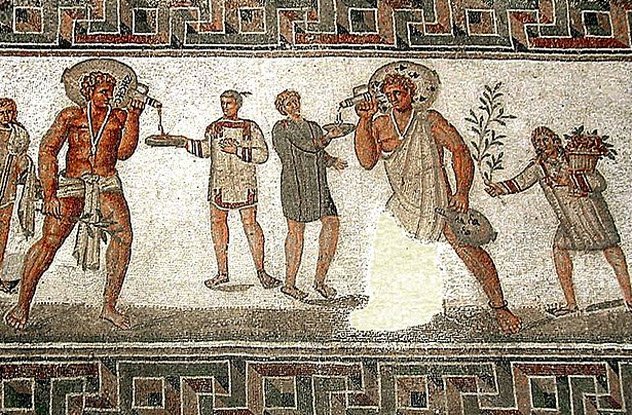

Cropsey wore street clothes and changed into a blue pinstripe suit in his office before giving his lectures. He kept his socks in the bottom drawer of his desk. On top of his steel filing cabinet, which contained Leo Strauss' private papers, was an 18th Century leather bound folio volume from Pierre Bayle's Dictionary, which contained Leo Strauss' private papers. I don't think these smelled of socks. The Bayle volume contained Bayle's article on Spinoza. Cropsey espoused his own brand of scepticism, so the Bayle was not surprising, nor was his reluctance to let non-Straussians peruse Strauss' correspondence. Cropsey had us read Aristotle's Politics, Plato's Meno, and Heidegger's Basic Problems of Phenomenology.The translation we used for Aristotle's Politics was translated by Straussian Carnes Lord--we called it the Lord edition. One of the essay questions Cropsey set for us related to what Aristotle meant by suggesting that there is such a thing as natural slavery--that some people are natural born slaves. As abhorrent as the subject was in itself, it was doubly horrible in light of the fact that it was being taught at the U. of C., which is adjacent to a ghetto on the south side of Chicago.

Meno wants to know what virtue is, and whether it can be taught. The failed geometry lesson Socrates facilitates with the slave is a device he uses--along with other things--to demonstrate that virtue cannot be taught.

Meno also wonders whether the capacity to govern human beings well is something that is common to all of us. Socrates suggests that a slave does not have this capacity--according to Socrates, slaves don't even have the capacity to govern themselves, which is why they need slaveholders to do that for them--so the capacity to govern well isn't common to everybody and is therefore not a fundamental human virtue. Socrates clearly believes that, like geometry, governing well--by analogy with geometry--cannot be taught to a slave either.

It is noteworthy that Cropsey did not choose to teach Plato's Protagoras--in the Protagoras, Socrates shows that practical virtues like justice and bravery can in fact be taught. In this case, it is tempting to imagine that Cropsey himself was not persuaded by Socrates' arguments in the Protagoras that virtue can be taught. Slaves are slavish for a reason. Cropsey came into class one day and made use of a word that is glossed in the Oxford English Dictionary. That word was slave gettable. So historic usage also supports the the concept of natural slavery.

It wasn't just that slaves couldn't be taught certain things like rulership. The virtue of governing well was something that could teased out of a someone with some admixture of gold in their soul. Others, who exemplified strong tribal spirit--had some contest of silver in their soul--could be trained to defend a city. They were not rulers, but "philosophical dogs" (Plato's term). Still others were suited to buy and sell--they had brazen souls. And so on down the line. Cropsey was not interested in the fate of those who had anything less than precious metals in their souls. He was interested in potential "gentlemen" (his word). The fact that many had base metal in their DNA was neither here nor there. Or, rather, it was not his concern.

Dissing lilies

During the course of the Plato lectures, Cropsey made what seemed to me then as odd comments. For example, he cast nasturtiums on the character of lilies. He did not invoke Matthew on this point, who asked us to "Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin." Instead, Cropsey told us that they were clever decoys for bees--who, if they were to smell the lilies, would turn around and fly away without pollinating them, and, in turn, the bees would make no honey. Honey was something good, but its origins were built on a lie told by the lily to the bee. So it was with the origin of cities, and the reason for the allegiance of citizens to the State--whether built upon stories of the shock and awe of mighty warriors, or on tales of how the gods must have smiled upon the very opulent, or on doctrines of the divine right of kings, people obey their rulers because of lies wrought upon their credulity. Rulers exploit a weakness in "baser" souls, who need to be led. Theoretically I should have been pleased to be have been let in on the secrets of lording it over others. As it was I was counting the days until I could leave Chicago and all of its big lies.Cadging Nazism?

When introducing Heidegger, Cropsey began: "I don't have to tell you that this man was a Nazi." But he (Cropsey) then proceeded to promote Heidegger as a worthy companion to the order of Great Books. Cropsey's choice of Heidegger's Basic Problems of Phenomenology was revealing. Heidegger's phenomenology lectures (1927) predated his inaugural lecture of 1929, and his lectures on metaphysics (given during the Nazi period in the Summer of 1935). Cropsey seemed to be suggesting--in his characteristic "I don't have to tell you" manner--that Heidegger's phenomenology was not tainted by the blatant Nazism of his metaphysics.

https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/hannah-arendt-on-eichmanna-study-in-the-perversity-of-brilliance/

To be continued.

Comments

Post a Comment