I never actually saw any philosophy students smoking Gitanes in the Philosophy department lounge--oh, yes, these were the bad old days, when people smoked everywhere--professors in bathrooms and classrooms, students in coffee lounges and corridors. The only place that was sacred--notice I don't say smoke free--was the library, where old rules prevailed. There the pledge I took--the oath I swore--to get my library card at the Bodleian Library in Oxford (note: Old Bod) seems to have made the trip to the New World. Smoke no cigarette, kindle no flame ... so I promised the Earl of Pembroke, who guarded the door.

Yes, they had treasures to protect, and there are miles of tunnels with book fetchers among cast iron stacks (book presses) designed by Gladstone in the New Bod, and luggers at their push carts--hurrying picked books and manuscripts to a waiting conveyor belt in response to reader requests--in triplicate--that traveled from the handwritten quarto sized guard book catalogues through the mammoth organ pipe system of pneumatic tubes to those who lived in a world of artificial light in the depths.

And if you dared, you could stand on a library ladder that looked like a medieval siege tower used to sack Jerusalem.

But I digress. I was talking about smoking in the Philosophy department at the University of Calgary back in the day. I never saw anyone smoking Gitanes, but there was plenty of posing by those who lived their lives like the light as air ash at the end of a cigarette barrel. Clearly knowledge or maybe just its appearance--or perhaps even power, or its fake, in its turn--grew from the barrel of a cigarette.

At the University of Chicago in the late 80s, Allan Bloom smoked camel shit ends--not that filters did anything anyway, but Bloom was making a statement. Reading the French of Montesquieu with his pince nez perched ever so precariously at the end of his nose, he alighted on a passage about the crazy behaviour of "Turkish" despots, who, paradoxically, represent even the most far flung peoples in their pseudopodian dominions, but never hear their screams. It was then Bloom deftly picked a Camel out of the soft pack nested in his left shirt pocket and with his other hand fumbled for a lighter in the patch pockets (both of them!) of his double breasted woolen jacket.

At the University of Chicago in the late 80s, Allan Bloom smoked camel shit ends--not that filters did anything anyway, but Bloom was making a statement. Reading the French of Montesquieu with his pince nez perched ever so precariously at the end of his nose, he alighted on a passage about the crazy behaviour of "Turkish" despots, who, paradoxically, represent even the most far flung peoples in their pseudopodian dominions, but never hear their screams. It was then Bloom deftly picked a Camel out of the soft pack nested in his left shirt pocket and with his other hand fumbled for a lighter in the patch pockets (both of them!) of his double breasted woolen jacket.

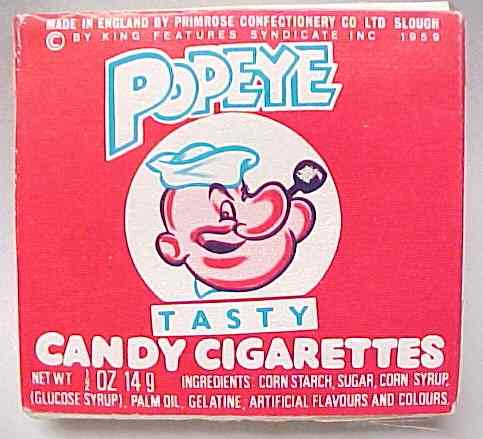

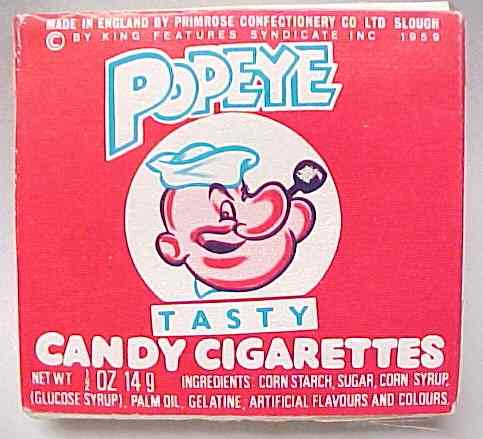

I think it was the tutor for Verena Huber-Dyson's formal logic course who liked to tease a Lucky Strike out of his candy pack (I thought they were chocolate cigarettes, but what did I know, I often settled for Popeye cigarettes as a kid, blowing powdered sugar and claiming it was smoke) and take a puff, especially when he invoked modus ponens and snuffed a proof the way night one way or another--even on equinox--kills the light.

I think it was the tutor for Verena Huber-Dyson's formal logic course who liked to tease a Lucky Strike out of his candy pack (I thought they were chocolate cigarettes, but what did I know, I often settled for Popeye cigarettes as a kid, blowing powdered sugar and claiming it was smoke) and take a puff, especially when he invoked modus ponens and snuffed a proof the way night one way or another--even on equinox--kills the light.

Verena herself--when trying to give up cigarettes--used to accidentally slip a stick of chalk between her lips and spit out the bits with disgust while turning to look at us after she completed one of her own proofs on a blackboard haunted by ghosts of charged brushes and greasy fists.

Verena was once married to Princeton mathematician Freeman Dyson and was equally brilliant. Trouble was, few of us were geniuses--we were not of the generation who were ever called gifted when we achieved--and her brilliance, while dazzling (that much we appreciated), was pretty much wasted on us, focused on half decent grades, as we then were. That didn't stop us from enjoying the walk from the Philosophy department in the lofty heights reached by the Environmental Design building to the basement of Social Sciences tower where she gave her lectures to students who generally had banded decks of punched IBM cards on their desks and Fortran and Cobol code on oversized unperforated sheets in their courier bags. Apart from the computer programmers, there were undergraduates trying to fulfill an Arts requirement for their degrees. Informal logic was apparently easier, but one never liked to waste a course.

Comments

Post a Comment